A string is a set of characters. Letters, numbers or symbols inside quotes form a string. We may use single or double quotes around

a string:

“Hello world.”

‘Hello world.’

Both of the above values are strings.

String is a sequence

A string is a sequence of characters. We can access the characters using their index. The index indicates the increasing number of the character in the sequence. In programming we usually start by 0, not 1.

name = 'Jack'

letter = name[0]

Now in letter there is the first character of name (‘J’).

J is the 0-th letter of name, ‘a’ is the 1-th and so on.

An index must be an integer value.

Change case methods

Python has a lot of methods to use with strings. A method is an action that Python can perform. There is always a dot (.) after the varable’s name to tell Python that the specific method applies on the particular variable. A method usually needs a set of parentheses, because methods accept additional data (parameters). These parameters are provided inside the parentheses. In case the method needs no parameters, the parenthses are empty.

See the following code.

message = "name surname"

print(message.title())

print(message.upper())

print(message.lower())

The .title() method outputs “Name Surname”.

The .upper() method outputs “NAME SURNAME”.

The .lower() method outputs “name surname”.

The len() function

We can get the number of characters in a string using the len() function.

name = 'Jack'

x=len(name)

print(x)

The code above will output 4. The string ‘Jack’ has 4 characters.

If you need to get the last character, you must ask for the name[len(name)-1]. As we have already mentioned the first character is the 0-th, so the last is len(name)-1.

name = 'Jack'

print(name[0], name[1], name[2], name[len(name)-1])

The code above will output the letters ‘J’, ‘a’, ‘c’ and ‘k’.

Alternatively, you can use negative indices, which count backward from the end of the string. The expression fruit[-1] yields the last letter, fruit[-2] yields the second to last, and so on.

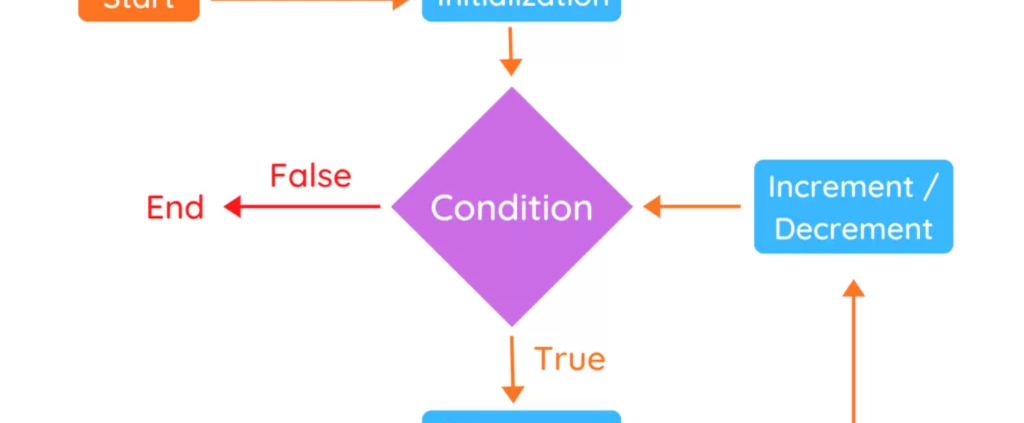

Traverse a String

A lot of computations involve processing a string one character at a time. Often they start at the beginning, select each character in turn, do something to it, and continue until the end. This pattern of processing is called a traversal. One way to write a traversal is with a while loop:

index = 0

while index < len(fruit):

letter = fruit[index]

print letter

index = index + 1

This loop traverses the string and displays each letter on a line by itself. The loop condition is index < len(fruit), so when index is equal to the length of the string, the condition is false, and the body of the loop is not executed. The last character accessed is the one with the index len(fruit)-1, which is the last character in the string.

Exercise 1

Write a function that takes a string as an argument and displays the letters backward, one per line.

Another way to write a traversal is with a for loop:

for char in fruit:

print char

Each time through the loop, the next character in the string is assigned to the variable char. The loop continues until no characters are left.

Τhe following example shows how to use concatenation (string addition) and a for loop to generate an series of similar words. This loop outputs the names Jack, Mack and Zack in order:

prefixes = 'JMZ'

suffix = 'ack'

for letter in prefixes:

print letter + suffix

The output is:

Jack

Mack

Zack

How to slice a String

A segment of a string is called a slice. Selecting a slice is similar to selecting a character:

s = 'Monty Python'

print s[0:5]

The output is Monty

The operator [n:m] returns the part of the string from the “n-eth” character to the “m-eth” character, including the first but excluding the last.

If you omit the first index (before the colon), the slice starts at the beginning of the string. If you omit the second index, the slice goes to the end of the string:

fruit = 'banana'

fruit[:3]

The output is ‘ban’

fruit[3:]

The output is ‘ana’

If the first index is greater than or equal to the second the result is an empty string, represented by two quotation marks:

fruit = 'banana'

fruit[3:3]

The output is ”

An empty string contains no characters and has length 0, but other than that, it is the same as any other string.

Exercise 3

Given that fruit is a string, what does fruit[:] mean?

Strings are immutable

It is tempting to use the [] operator on the left side of an assignment, with the intention of changing a character in a string. For example:

>>> greeting = 'Hello, world!'

>>> greeting[0] = 'J'

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

The “object” in this case is the string and the “item” is the character you tried to assign. For now, an object is the same thing as a value, but we will refine that definition later. An item is one of the values in a sequence.

The reason for the error is that strings are immutable, which means you can’t change an existing string. The best you can do is create a new string that is a variation on the original:

>>> greeting = 'Hello, world!'

>>> new_greeting = 'J' + greeting[1:]

>>> print new_greeting

Jello, world!

This example concatenates a new first letter onto a slice of greeting. It has no effect on the original string.

Searching

What does the following piece of code do?

def find(word, letter):

index = 0

while index < len(word):

if word[index] == letter:

return index

index = index + 1

return -1

The function takes a word and a character and finds the index where that character appears in the word. If the character is not found, the function returns -1.

This is the first example we have seen of a return statement inside a loop. If word[index] == letter, the function breaks out of the loop and returns immediately.

If the character doesn’t appear in the string, the program exits the loop normally and returns -1.

This pattern of computation—traversing a sequence and returning when we find what we are looking for—is called a search.

Exercise 4

Modify find so that it has a third parameter, the index in word where it should start looking.

Looping and counting

The following program counts the number of times the letter a appears in a string:

word = ‘banana’

count = 0

for letter in word:

if letter == ‘a’:

count = count + 1

print count

This program demonstrates another pattern of computation called a counter. The variable count is initialized to 0 and then incremented each time an a is found. When the loop exits, count contains the result—the total number of a’s.

Exercise 5 Encapsulate this code in a function named count, and generalize it so that it accepts the string and the letter as arguments.

Exercise 6Rewrite this function so that instead of traversing the string, it uses the three-parameter version of find from the previous section.

String methods

A method is similar to a function—it takes arguments and returns a value—but the syntax is different. For example, the method upper takes a string and returns a new string with all uppercase letters:

Instead of the function syntax upper(word), it uses the method syntax word.upper().

>>> word = ‘banana’

>>> new_word = word.upper()

>>> print new_word

BANANA

This form of dot notation specifies the name of the method, upper, and the name of the string to apply the method to, word. The empty parentheses indicate that this method takes no argument.

A method call is called an invocation; in this case, we would say that we are invoking upper on the word.

As it turns out, there is a string method named find that is remarkably similar to the function we wrote:

>>> word = ‘banana’

>>> index = word.find(‘a’)

>>> print index

1

In this example, we invoke find on word and pass the letter we are looking for as a parameter.

Actually, the find method is more general than our function; it can find substrings, not just characters:

>>> word.find(‘na’)

2

It can take as a second argument the index where it should start:

>>> word.find(‘na’, 3)

4

And as a third argument the index where it should stop:

>>> name = ‘bob’

>>> name.find(‘b’, 1, 2)

-1

This search fails because b does not appear in the index range from 1 to 2 (not including 2).

Exercise 7 There is a string method called count that is similar to the function in the previous exercise. Read the documentation of this method and write an invocation that counts the number of as in ‘banana’.

Exercise 8 Read the documentation of the string methods at http://docs.python.org/2/library/stdtypes.html#string-methods. You might want to experiment with some of them to make sure you understand how they work. strip and replace are particularly useful.

The documentation uses a syntax that might be confusing. For example, in find(sub[, start[, end]]), the brackets indicate optional arguments. So sub is required, but start is optional, and if you include start, then end is optional.

The in operator

The word in is a boolean operator that takes two strings and returns True if the first appears as a substring in the second:

>>> ‘a’ in ‘banana’

True

>>> ‘seed’ in ‘banana’

False

For example, the following function prints all the letters from word1 that also appear in word2:

def in_both(word1, word2):

for letter in word1:

if letter in word2:

print letter

With well-chosen variable names, Python sometimes reads like English. You could read this loop, “for (each) letter in (the first) word, if (the) letter (appears) in (the second) word, print (the) letter.”

Here’s what you get if you compare apples and oranges:

>>> in_both(‘apples’, ‘oranges’)

a

e

s

String comparison

The relational operators work on strings. To see if two strings are equal:

if word == ‘banana’:

print ‘All right, bananas.’

Other relational operations are useful for putting words in alphabetical order:

if word < ‘banana’:

print ‘Your word,’ + word + ‘, comes before banana.’

elif word > ‘banana’:

print ‘Your word,’ + word + ‘, comes after banana.’

else:

print ‘All right, bananas.’

Python does not handle uppercase and lowercase letters the same way that people do. All the uppercase letters come before all the lowercase letters, so:

Your word, Pineapple, comes before banana.

A common way to address this problem is to convert strings to a standard format, such as all lowercase, before performing the comparison. Keep that in mind in case you have to defend yourself against a man armed with a Pineapple.